This post was first published on The Oil Drum. Read there for comments.

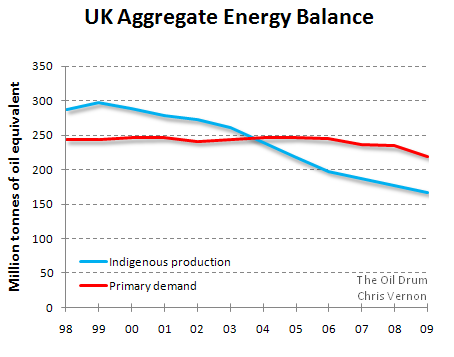

The UK Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) published their quarterly Energy Trends document last week. It covers up to the first quarter 2010. The key points:

- Total energy production in Q1 2010 was 6.5% lower than in the first quarter of 2009.

- Oil production fell by 6% compared to the first quarter of 2009.

- Natural gas production was 9% lower compared with the first quarter of 2009. The UK was a net importer of gas in the first quarter of 2010 by 155 TWh compared with 106 TWh in the first quarter of 2009.

- Coal production was 12.5% lower than a year earlier.

- Nuclear’s supply increased by 1% on the first quarter of 2009.

- Wind, hydro and other renewables supplied 6.5% less electricity than in the same period last year, with hydro down 44% as a result of less rainfall.

- Final energy consumption rose by 4% between the first quarter of 2009 and the first quarter of 2010, with rises in all sectors except transport which fell mainly due to the adverse weather conditions.

- Gas demand was 13% higher than a year earlier.

- Electricity consumption was 2.5% higher in the first quarter of 2010 compared to the same period last year.

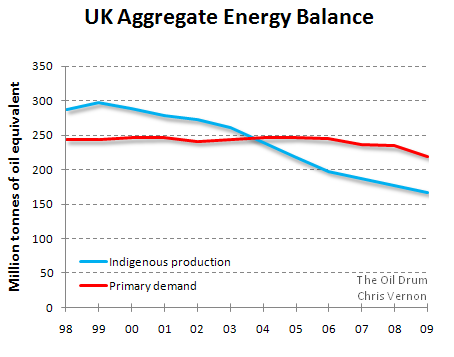

It’s a familiar story: every year the UK’s primary energy production declines significantly. Today, primary energy production is almost half what it was at the peak just a decade ago. Has any other country, let alone major economy experienced such a speed and magnitude shift in its energy system outside wartime?

The rises in the demand data above are largely due to the colder winter and a degree of recovery from the recession. One could argue the decline in indigenous production played a role in the recession. If it did, I suggest it was a small role.

Data from DUKES 1.1-1.3.

The annual energy deficit in 2008 was 57.5 million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe). That’s a lot of energy to import. The breakdown of this deficit in 2008 was 42% coal, 36% gas and 19% oil. Let’s just make a quick estimation on how much this is costing:

|

Fuel

|

Percentage

|

Deficit (mtoe)

|

2008 Cost/toe (£)

|

Total Cost (£bn)

|

| Coal |

42% |

24.15 |

115 |

2.77 |

| Gas |

36% |

20.70 |

191 |

3.95 |

| Oil |

19% |

10.92 |

287 |

3.14 |

| Total |

9.86

|

UK Energy Deficit 2008. Energy data from DUKES 1.1-1.3. Prices from QEP 3.2.1.

In 2008 the gap cost the UK approximately £10 bn. Fuel prices were a little lower in 2009 (especially coal and gas at -17% and -15% respectively) and the recession closed the gap from 57.5 to 53 mtoe. A few years ago the energy sector was a net source of income for the UK. No longer. The government deficit and the growing debt is receiving the media attention, this energy deficit, now it its fifth year remains largely ignored.

Following the May election, the UK now has a new Energy Minister:

Chris Huhne MP, Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change.

On the 24 June 2010, Huhne gave a speech to the Economist UK Energy Summit, it can be watched here: VIDEO

Did he address the chart above, our energy deficit in the same way chancellor George Osborne had addressed the fiscal deficit in his emergency budget earlier in the week? Well no, not directly. Economic recovery, energy security and climate stabilisation were identified as the key challenges. He isn’t a politician to question growth but did address the type of growth. “…dependence on fossil fuel would be folly. It would make us vulnerable to oil price spikes and volatility.” He called for a decarbonised economy stimulating growth and delivering on climate change and energy security. Sounds good but surely it is having one’s cake and eating it?

After stressing the urgency and seriousness of climate change Huhne addressed energy security. “It is vital we make the most of our domestic oil and gas assets…” indicating at least 20 billion barrels oil equivalent remain in UK waters and that we must continue to invest in exploration. His first mutually exclusive objective of delivering growth through decarbonising is now joined by his second of addressing climate change whist continuing to explore for new fossil fuel resources.

£200 bn of energy investment was said to be needed over the next decade, largely to replace existing assets. On new nuclear, Huhne stressed it will go ahead, but only if it can do so with no public subsidy. In my opinion this all but rules out nuclear as there is little precedent for wholly privately funded nuclear, but we shall have to wait and see. Whatever happens, it will be late with respect to the decommissioning schedule of the existing fleet of nuclear power stations.

Efficiency was described as the fourth energy resource (relegating nuclear and renewables to 5th and 6th?)–the cheapest way of closing the energy gap between demand and supply – “the Cinderella of the energy ball”. Smart meters and grids received a nod but he focused mainly on the existing aged housing stock. “Most of the homes in use in 2050 have already been built … we used more energy heating our homes than Sweden, where average January temperatures are 7 degrees Celsius lower than ours.” Addressing existing homes will be Huhne’s flagship programme. He’s talking about insulating millions of homes. It seems the improvements will be funded at least in part through the energy savings and recovered directly from household utility bills.

“The era of cheap energy is over. …tomorrow’s energy bills will undoubtedly be higher”

When asked about the lights going out, he ruled out wind and nuclear coming to the rescue due to the timeframe, but he stated gas fired power stations can be built in 18 months and assured us the lights wouldn’t go out on his watch. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) was described as vital to meeting climate objectives whilst keeping the lights on.

So in summary, Huhne didn’t address the fundamental peaking of energy supplies which surely should be the key driver for national energy policy today. The inconsistencies of shooting for growth whilst reducing energy use along with addressing climate change (by which I can only assume he means reducing carbon emissions) while encouraging future exploration for oil and gas are glaring. Meinshausen et. al. showed in their Nature paper last year the world has more than enough proved fossil fuel reserves already from a climate change point of view without having to discover more. His enthusiasm for CCS is also worrisome and I would see as largely incompatible with energy peaking scenarios. His focus on energy efficiency and especially domestic energy use is positive though. However there was no mention of transport at all.

New government, new minister but we still seem little closer to recognising the challenges ahead.